Here’s the thing about Clair Obscur: Expedition 33 – it showed up to the party fashionably late, wearing a Belle Époque coat that somehow made everyone else’s outfits look cheap. While the rest of the gaming industry spent 2025 frantically chasing live-service dollars and AI-generated content, this French studio called Sandfall dropped what can only be described as a love letter written in blood to the idea that games can still be art.

And before you roll your eyes at another “games as art” hot take, stick with me. This isn’t pretentious nonsense – it’s the real deal, arriving at exactly the moment we needed it most.

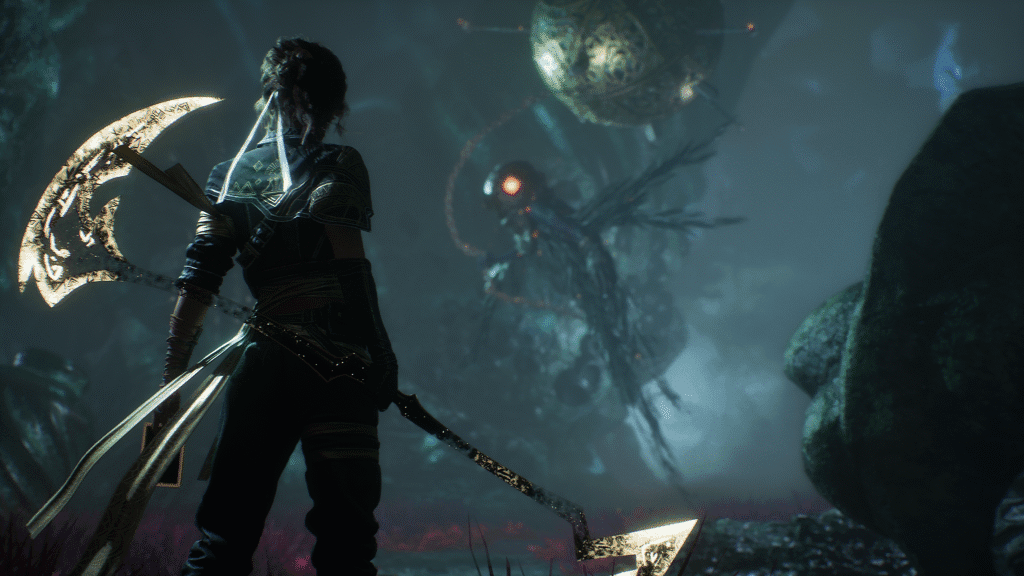

Picture this: April 2025, the gaming landscape looking like a battlefield. Major studios haemorrhaging talent, AI threatening to replace human creativity, and players so starved for authentic experiences they’ll mob-rush any indie game that shows a hint of genuine personality. Into this chaos walks Expedition 33, a turn-based RPG that dares to ask the most uncomfortable question possible: What if your entire society was built around accepting inevitable death?

The timing couldn’t be more perfect, or more devastating. We’re living through our own slow-motion apocalypse – climate change, democratic backsliding, the steady erosion of everything that once felt permanent. And here comes this game about a city where everyone knows exactly when they’ll die, where entire communities gather to throw beautiful going-away parties for the condemned, where hope itself becomes a form of performance art.

But here’s what makes Expedition 33 more than just pandemic anxiety wrapped in pretty pixels: it refuses to comfort you. Most games, even the dark ones, eventually hand you a sword and tell you to fix everything. This game looks you dead in the eye and says, “What if some problems can’t be solved? What if heroism is just another way of avoiding the truth?”

That’s not nihilism talking – that’s French existentialism filtered through six years of obsessive game development, born from Guillaume Broche’s pandemic-fueled late-night Unreal Engine binges. And it shows. Every frame of this game feels like it was painted by someone who understands that beauty and tragedy aren’t opposites but dance partners.

My argument is simple: Clair Obscur: Expedition 33 isn’t just reflecting our cultural moment – it’s diagnosing it. This is what happens when genuinely talented people get fed up with corporate game development and decide to make something that matters. It’s a mirror, a manifesto, and maybe most importantly, a reminder that mid-budget passion projects can still break your heart in ways that hundred-million-dollar blockbusters can’t touch.

The question isn’t whether this game will age well. The question is whether we’re ready for what it’s trying to tell us.

The Pandemic Game We Didn’t Know We Needed

Let’s talk about timing, because Expedition 33’s origin story reads like a perfect metaphor for creative survival during impossible circumstances. Guillaume Broche, trapped in lockdown like the rest of us, channelling his restless energy into nocturnal game development sessions that he admits became “toxic” in their intensity. The result? A game about people living under the constant shadow of predetermined death dates that feels less like fantasy and more like the most honest pandemic art we’ve gotten.

The Gommage ceremony – where entire communities throw elaborate farewell parties for people about to vanish – isn’t subtle allegory. It’s exactly how we’ve been processing mass death for the past few years. The ritualized celebration, the community gathering around loss, the way normal life continues right up until the moment it doesn’t. If you lived through 2020-2022, you know this feeling in your bones.

But the game’s genius lies in how it transforms collective mourning into something beautiful rather than just tragic. These aren’t grim funeral processions but festivals of memory, celebrations of what someone meant before they’re gone. It’s grief as performance art, and it works because it acknowledges what we all learned during the pandemic: sometimes ritual is the only thing standing between us and complete emotional collapse.

The 67-year cycle of the Paintress creates another layer of meaning that hits different in 2025. Each generation inherits the failures of the previous one, adds their own mistakes to the pile, then sends the next batch of young people off to fix problems that might be fundamentally unfixable. Sound familiar? Climate change, anyone? Democratic institutions? The housing crisis?

Late-Stage Capitalism as Horror Fantasy

Strip away the Belle Époque aesthetics and mystical paintbrushes, and Expedition 33 reveals itself as a surprisingly sharp critique of how modern societies organize suffering. The expedition system is basically the gig economy with prettier costumes – volunteers taking on dangerous, likely fatal work for the promise of solving systemic problems they didn’t create.

Think about it: every expedition is essentially a startup pitch. Young, idealistic people convinced they can disrupt death itself if they just work hard enough and believe strongly enough. The fact that no one has ever returned successful doesn’t matter – there’s always another batch of volunteers ready to try a slightly different approach. It’s Uber, but for martyrdom.

The game’s development story reinforces this reading beautifully. Sandfall Interactive formed during the pandemic exodus from major studios, with talented developers abandoning corporate security to pursue passion projects under precarious conditions. Even their success story required external publishing support and contractor assistance, proving that creative autonomy remains mostly illusory. You can escape the corporate machine, but you can’t escape the market.

What’s particularly brutal is how the game treats individual heroism as a form of systemic pressure release. Each expedition allows society to maintain the illusion that solutions exist while ensuring those solutions remain safely out of reach. It’s not that the heroes aren’t brave or capable – it’s that the system is designed to consume heroes while preserving itself.

The Aesthetics of Optimism Gone Wrong

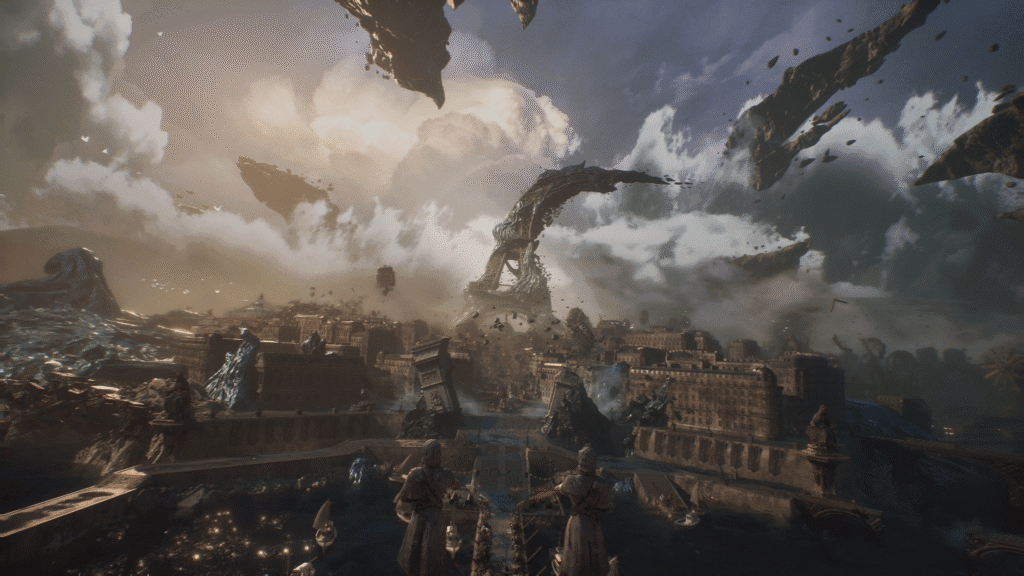

The Belle Époque setting isn’t just visual flavour – it’s cultural archaeology. The period from 1871 to 1914 represents the last moment of European confidence before everything went to hell, when people genuinely believed art and technology could solve humanity’s fundamental problems. Sound familiar?

By filtering this aesthetic through supernatural corruption, Expedition 33 creates a visual argument about our current technological optimism. All those beautiful Art Nouveau curves and rationalist architecture start looking a lot less stable when you add mystical decay and existential dread. It’s like seeing Instagram’s tech utopia filtered through pandemic reality – all the pretty surfaces hiding structural rot.

The colour palette does heavy lifting here, shifting from warm golds during normal life to ethereal blues during supernatural encounters. It’s visual language that communicates safety versus danger without hitting you over the head with it. The gradual shift toward cooler tones as characters approach their death dates creates subliminal anxiety that works on your nervous system before your conscious mind catches up.

But here’s what I love most about the game’s visual philosophy: it never apologizes for being beautiful. In an era when “serious” games often default to gritty realism or cyberpunk neon, Expedition 33 insists that gorgeous art can carry devastating themes. Beauty isn’t escapism – it’s how we make unbearable truths bearable enough to contemplate.

Political Undertones Without Political Theatre

One of the smartest things Expedition 33 does is avoid explicit political messaging while building its entire structure on political assumptions. The expedition system is basically ritualized democracy – regular cycles of sending representatives to address collective problems, knowing they’ll probably fail, but maintaining the process anyway because it beats admitting helplessness.

The class dynamics are impossible to ignore once you start looking. Wealthy Lumière citizens don’t volunteer for expeditions; they fund them. Working-class heroes sacrifice themselves for problems created by institutional failures while the comfortable classes provide moral support from a safe distance. It’s climate activism in microcosm – those least responsible bearing the greatest cost while those most responsible maintain plausible deniability through charitable donations.

The diversity controversy surrounding the game’s all-white cast reveals additional cultural tensions. Critics noting the lack of racial representation met pushback from players defending “historical accuracy” to Belle Époque France – despite the game featuring literal magic paintbrushes that erase people from existence. This argument illuminates how “authenticity” becomes a weapon in representation debates, with artistic vision sometimes clashing with inclusivity expectations in ways that satisfy nobody.

What’s fascinating is how the game handles other forms of identity with much more sophistication. Class dynamics, generational conflict, and gender roles all receive nuanced treatment that suggests the developers aren’t indifferent to representation politics – they just made different choices about which identities to center.

The Grief Industry

Perhaps most relevant to our current moment is how Expedition 33 examines grief as social performance. The Gommage ceremonies aren’t just community rituals – they’re elaborate productions requiring costumes, music, choreography, and emotional labour from everyone involved. Mourning becomes work, and like all work under capitalism, it demands optimization.

This hits particularly hard after years of pandemic grief, where we’ve watched entire industries emerge around processing collective trauma. Wellness apps, grief podcasts, trauma-informed everything – grief has become another market to capture and monetize. The game’s beautiful ceremonies start looking more sinister when you realize they’re not just about honouring the dead but managing the living.

The expedition mythology serves a similar function. Each failed expedition becomes a heroic story that justifies the next attempt while obscuring the systemic problems that make expeditions necessary. It’s like our relationship with startup culture – every failure becomes inspiration for the next entrepreneur, while the fundamental absurdity of the system remains unexamined.

Who Gets to Exist in This World?

Here’s where things get spicy. Expedition 33’s approach to representation has sparked the kind of heated online debates that make you remember why comment sections were a mistake. The game features an entirely white cast in its Belle Époque fantasy setting, and boy, did people have opinions about that.

Now, before the pitchforks come out – this isn’t just another “historically accurate” dodge. The developers made deliberate choices here, and those choices reveal something interesting about how we navigate authenticity versus inclusivity in 2025. Critics rightfully pointed out that fantasy worldbuilding offers perfect opportunities to reimagine historical limitations rather than reproduce them. Why preserve Belle Époque demographics while throwing in magic paintbrushes that erase people from existence?

But here’s what’s fascinating: the game’s other identity work is actually pretty sophisticated. Take Maelle, who could’ve been another cookie-cutter healer but instead becomes this wonderfully aggressive, complex character who drives major plot developments. The women in Expedition 33 aren’t relegated to emotional support roles – they’re the ones making the hard decisions and dealing with the consequences.

The class dynamics, though? Chef’s kiss. This is where the game’s representation politics get genuinely interesting. The expedition system functions as ritualized class warfare, where working-class volunteers sacrifice themselves for problems created by institutional failures while wealthy Lumière citizens provide funding and moral support from a safe distance. It’s climate activism in microcosm – those least responsible bearing the greatest cost while those most responsible maintain plausible deniability.

The absence of LGBTQ+ representation feels more like creative focus than deliberate exclusion, but it still stands out in an era when most RPGs include at least token queer characters. This choice positions Expedition 33 as either refreshingly unburdened by contemporary identity politics or frustratingly indifferent to them, depending on your perspective.

What the game does brilliantly is economic representation. Every visual detail reinforces class hierarchy – expedition members wear practical, weathered clothing while Lumière’s citizens sport elaborate Belle Époque fashion. This isn’t just aesthetic choice but cultural commentary on how societies aestheticize inequality, making poverty appear noble while rendering wealth invisible through normalization.

Art & Aesthetics as Cultural Statements

If Expedition 33 were a person, it would be that friend who went to art school, actually learned something useful, and now casually drops references to chiaroscuro techniques while making you feel both impressed and slightly inadequate. This game doesn’t just look pretty – it argues with you through visual language.

The Belle Époque setting isn’t nostalgic window dressing. This period (1871-1914) represents humanity’s last moment of genuine optimism before the twentieth century’s brutal reality check. Art Nouveau curves, gas-lit boulevards, the whole aesthetic package of a society that believed beauty could transform the world. By filtering this through supernatural corruption, the game creates visual metaphor for how utopian dreams encounter existential reality.

The chiaroscuro philosophy runs deeper than surface prettiness. Every scene operates on light-versus-shadow contrast that serves both formal and thematic purposes. It’s not just that the game looks dramatic – it’s arguing that truth emerges through contrast, that beauty and horror are dance partners rather than opposites.

The architectural design deserves special attention. Buildings blend organic Art Nouveau curves with geometric rationalism, creating structures that appear simultaneously beautiful and unstable. It’s civilization built on aesthetically pleasing but fundamentally unsound foundations – a visual metaphor so on-the-nose it would be embarrassing if it weren’t so effectively executed.

The colour work operates on multiple symbolic levels. Golden hours of normal Lumière life contrast with ethereal blues of supernatural encounters, creating emotional landscapes that manipulate player feelings before conscious processing kicks in. The gradual shift from warm to cool tones as characters approach predicted death dates creates subliminal anxiety that reinforces narrative themes without exposition dumps.

What truly sets Clair Obscur: Expedition 33’s soundtrack apart is how it refuses to be mere wallpaper. Composer Lorien Testard mixes Belle Époque waltzes with glitch-stuttered synths, creating a living, breathing score that feels like Parisian gas-lamps flickering over a cyberpunk skyline. Each cue teases you with gilded hope, then undercuts it with a minor-key shiver, mirroring the game’s dance between beauty and dread. The music swells into orchestral grandeur when the expedition glimpses salvation, then collapses into a single cracked cello harmonic as reality closes in – reminding you that optimism is fragile, but so, too, is despair. It’s the rare game album that demands headphones, a quiet room, and your full emotional attention; layered listens reveal the hiss of vintage wax cylinders under pristine strings, as if history itself were haunting the mix. This isn’t just a soundtrack – it’s the game’s second script, whispering what words leave unsaid and making every step through Lumière’s streets feel eerily, achingly alive.

The game’s environmental storytelling rewards careful observation in ways that feel genuinely literary rather than game-ified. Private homes reveal character personalities through furnishing choices and decorative objects. These aren’t just background details but psychological archaeology – evidence of interior lives extending beyond player interaction.

Mechanics as Metaphor: Gameplay That Comments on Society

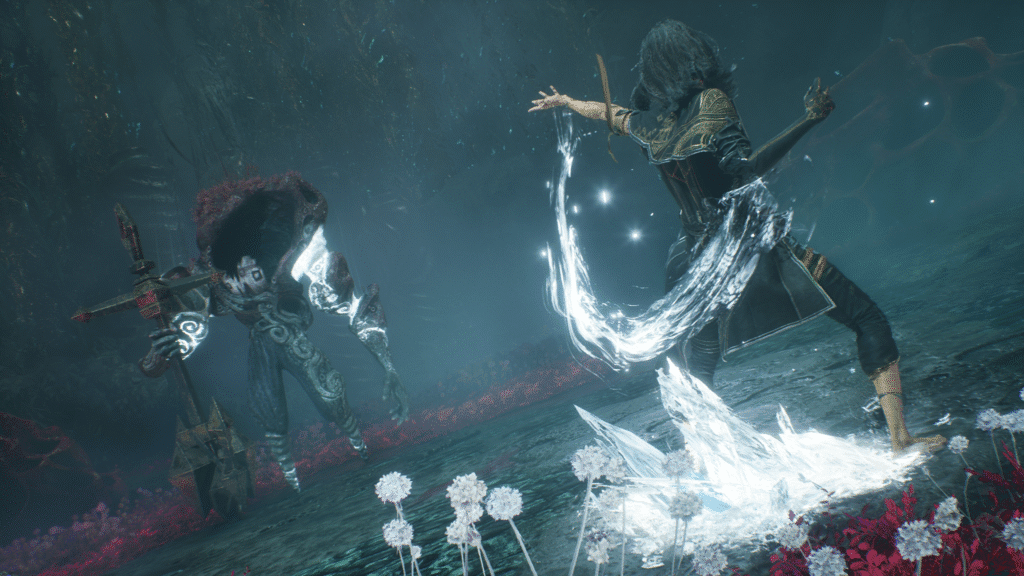

This is where Expedition 33 gets really clever. The turn-based combat system – which could’ve been purely nostalgic pandering to JRPG fans – actually functions as social commentary disguised as game mechanics.

The expedition structure itself mirrors modern gig economy logic. Volunteers undertake dangerous, likely fatal work for the promise of solving systemic problems they didn’t create. Each expedition is essentially a startup pitch: young, idealistic people convinced they can disrupt death itself if they just work hard enough and believe strongly enough. The fact that no expedition has ever returned successful doesn’t matter – there’s always another batch of volunteers ready to try a slightly different approach.

Combat timing mechanics require precise input during both attacks and defense, creating gameplay that demands constant attention and split-second decision-making. This isn’t just mechanical challenge – it’s metaphor for how survival under impossible circumstances requires perpetual vigilance. There’s no autopilot mode, no coasting through encounters. Every moment demands active engagement, mirroring the psychological state of people living under existential threat.

The resource management avoids typical JRPG grinding mechanics that would undermine thematic coherence. Instead of endlessly accumulating power and wealth, characters work within finite systems that emphasize careful allocation over pure accumulation. It’s anti-capitalist game design that prioritizes sustainability over growth.

The party dynamics reflect collective action challenges. Success requires coordination between characters with different abilities and motivations, but individual excellence can’t overcome systematic problems. It’s a gameplay argument for solidarity that feels earned rather than preachy because it emerges from mechanical necessity rather than narrative lecturing.

A Product of Its Time, or a Rebel?

Expedition 33 arrived during one of the gaming industry’s most turbulent periods, and its existence feels almost miraculous given the circumstances. While major studios were laying off thousands of developers, chasing live-service monetization, and generally forgetting why people play games in the first place, Sandfall Interactive was quietly proving that mid-budget passion projects could still matter.

The game’s development story reads like industry resistance literature. Guillaume Broche’s pandemic-era exodus from Ubisoft, channelling creative frustration into nocturnal Unreal Engine sessions that became “toxic” in their intensity. The team’s emphasis on creative control and intimate collaboration stands in stark contrast to crunch-culture horror stories emanating from major developers.

The “30-person team” mythology that initially surrounded the game reveals industry anxieties about scale and authenticity. Early coverage suggested this small French studio had somehow produced AAA-quality content with indie resources, triggering both admiration and skepticism. The reality – external contractors, publisher support, and careful scope management – proves that creative autonomy remains mostly illusory even for successful independents.

Will This Game Age Well?

Predicting artistic longevity is fool’s work, but Expedition 33 has several factors working in its Favor. Unlike games that chase contemporary trends, it builds on timeless artistic foundations that have already survived multiple cultural shifts.

The Belle Époque aesthetic provides historical anchor that should age gracefully. Unlike cyberpunk neon or military shooter grit, Art Nouveau curves and chiaroscuro lighting draw from centuries-old artistic traditions. These influences survived the transition from painting to cinema to digital art, suggesting they’ll outlast current gaming fashion cycles.

Narrative themes around mortality, artistic legacy, and collective trauma feel unfortunately evergreen. Climate change, democratic backsliding, and technological disruption ensure these concerns will remain relevant for decades. The game’s refusal to provide easy solutions actually strengthens its long-term prospects – it’s asking questions rather than providing dated answers.

Historical precedents suggest mid-budget artistic projects often age better than their AAA contemporaries. Persona 4, Nier: Automata, and Disco Elysium all found broader audience’s years after release through word-of-mouth and cultural revaluation. Expedition 33 has similar qualities: distinctive vision, cultural sophistication, and themes that reward multiple playthroughs.

The game’s cultural specificity – its deeply French sensibility and European artistic references – might actually aid longevity. Regional authenticity often translates better across time than globalized homogeneity. Future players may appreciate its cultural particularity more than contemporary audiences focused on broader appeal.

Conclusion: What This Game Says About Us

So here we are, back where we started, staring at this beautiful, melancholy artifact that somehow emerged from our chaotic cultural moment. Clair Obscur: Expedition 33 didn’t just predict our anxieties – it diagnosed them with surgical precision.

This game arrived exactly when we needed it most: a moment when authentic artistic vision felt endangered by corporate algorithms and AI generation. It proved that small teams with clear vision could still create experiences that matter, that beauty and meaning hadn’t been completely commodified out of existence.

The game’s treatment of mortality and legacy speaks directly to our pandemic-altered relationship with death and meaning. We’ve all lived through the Gommage ceremonies now – community gatherings to process loss while maintaining normal life rhythms. We understand how ritual becomes the only barrier between grief and complete emotional collapse.

More importantly, Expedition 33 offers a model for cultural preservation that feels both urgent and hopeful. The game doesn’t just reference Belle Époque aesthetics – it reanimates them for contemporary purposes, proving that historical engagement can honour sources without becoming trapped by them.

The industry implications are equally significant. This game demonstrates that artistic ambition and commercial success aren’t mutually exclusive, even in an era dominated by live-service monetization. It’s proof that audiences still hunger for complete, coherent visions over perpetual content streams.

But perhaps most importantly, Expedition 33 refuses to comfort us with false hope while avoiding nihilistic despair. It acknowledges that some problems can’t be solved through individual heroism while insisting that beauty and dignity remain possible even under impossible circumstances.

The question isn’t whether this game will age well – it’s whether we’re ready for what it’s trying to tell us. In a world increasingly organized around systematic erasure of inconvenient truths, Expedition 33 insists that art’s primary function is preservation: keeping alive what power wants forgotten, maintaining space for beauty in the face of relentless optimization.

If you love this game, what does that say about you? Maybe that you’re tired of being sold solutions to problems that require collective action. Maybe that you still believe games can be more than entertainment, that interactive media has untapped potential for cultural dialogue and emotional sophistication.

Or maybe you just recognize good art when you see it, and you’re grateful someone still cares enough to make it properly.

Final Score: 4.8/5

This review of Clair Obscur: Expedition 33 is based on the PC version, with a code provided by the game’s publisher. It’s available on PS4, PS5, Xbox One, Xbox Series X/S, Switch and PC. Special Thanks to Guillotine.