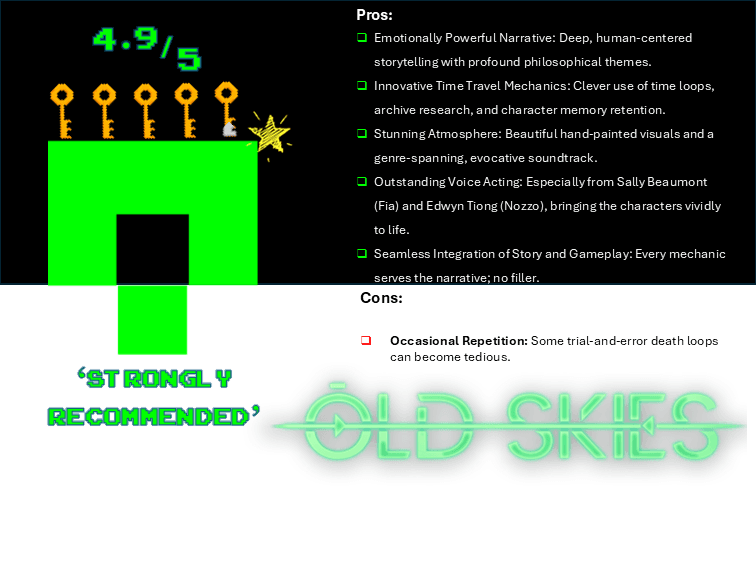

Old Skies Is the Most Human Time Travel Game Ever Made

I didn’t intend to fall in love with Old Skies. I really didn’t. Like many of you, I judged too quickly. At first glance, Wadjet Eye’s latest seemed like a quaint curiosity—another pixel-hued point-and-click from a niche corner of indie gaming. But as I sit here now, clocking in at 13 hours of gameplay and nearly double that in note-taking, reflecting, and re-playing, I find myself haunted—in the best way—by the game’s soul-deep resonance. I pushed back deadlines, rescheduled meetings, and sank into the role of Fia Quinn not just as a player but as a companion in her time-tossed life.

There’s a difference between playing a game and living in it. This wasn’t a casual click-through. This was an immersion, an unraveling. The hours didn’t simply pass—they folded, twisted, and looped like the very timelines Old Skies dares to dissect. This review is not just a critique but a love letter to the kind of game we so rarely get anymore: bold in narrative, intimate in theme, and devastatingly human in execution.

There’s a moment in Old Skies—and you’ll know it when it happens—where the game stops being about “mechanics” and becomes about meaning. For me, it was midway through a chapter set just before September 11, 2001. A client, a retired cop, is trying to undo a private tragedy that history has all but erased. And there you are, time-locked, watching helplessly as the familiar skyline looms with the weight of impending catastrophe.

You’re not there to change the event. You can’t. And that’s the genius of it. This isn’t a power fantasy. This is a meditation on helplessness, memory, and the terrible beauty of impermanence. Suddenly, the game’s loop-based structure, its light puzzles, even its modest visual design—everything coalesces into an emotionally wrenching tableau.

From that point on, I played not just with my mouse but with my heart.

Stories Woven Through Time

Fia Quinn isn’t your typical video game protagonist. She’s not saving the world, not uncovering grand conspiracies, not hunting demons. She’s doing something far harder: she’s surviving change. A time agent in the year 2062, Fia’s job is to accompany wealthy clients on sanctioned trips to the past. For a price, they can relive a memory, ask a dead loved one a question, or retrieve a forgotten masterpiece—so long as their actions don’t disrupt the fragile web of causality.

Each of the game’s seven chapters is a story unto itself—a microcosm of yearning, regret, and hope. There’s the boxer desperate to rewrite her legacy. The artist searching for a piece of his soul in pre-war New York. The grieving woman trying to prevent a friend’s murder the day before 9/11. These stories are told with nuance and restraint, more Before Sunrise than Back to the Future.

But Old Skies isn’t satisfied with anthology alone. Slowly, subtly, a grander thread emerges—Fia’s own journey from observer to participant. Chronolocked against the shifting tides of history, she begins to crack under the weight of what she’s seen and lost. Love that never happened. Lives that flicker in and out of reality. “Focus on the job,” she tells herself, mantra-like. But that job becomes a mirror, reflecting everything she’s missing.

The game dares to ask: If you remembered every version of your life, which one would you choose?

Mechanics as Metaphor

At its core, Old Skies adheres to the point-and-click formula: explore environments, collect items, solve puzzles. But it’s the how and why that elevates it. Each mechanic is in service of story. The Historical Archive—a searchable database of everyone who ever lived—isn’t just a puzzle tool. It’s a philosophical challenge. What does it mean to know everything about someone before they know it themselves? How do you wield that power responsibly?

Death, too, is gamified with elegance. Fia will die—shot, strangled, blown up—and every death resets the loop. But knowledge carries over. You learn through failure, not punishment. It’s a system that rewards curiosity and persistence, not pixel-perfect timing. And like everything else in Old Skies, it serves a deeper purpose: illustrating the cost of knowing too much, and changing too little.

Aesthetic Intimacy: Art Direction and Visual Storytelling

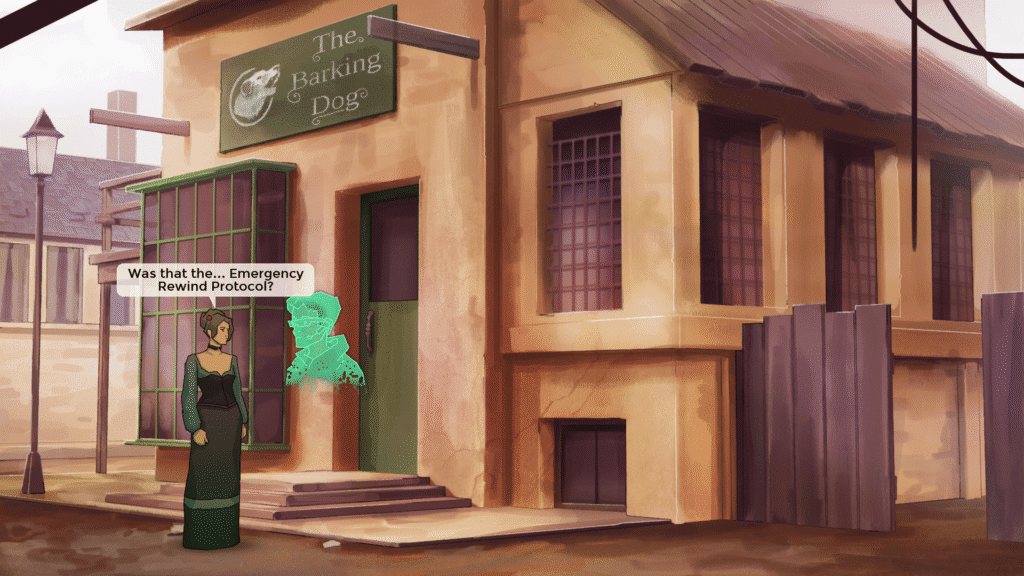

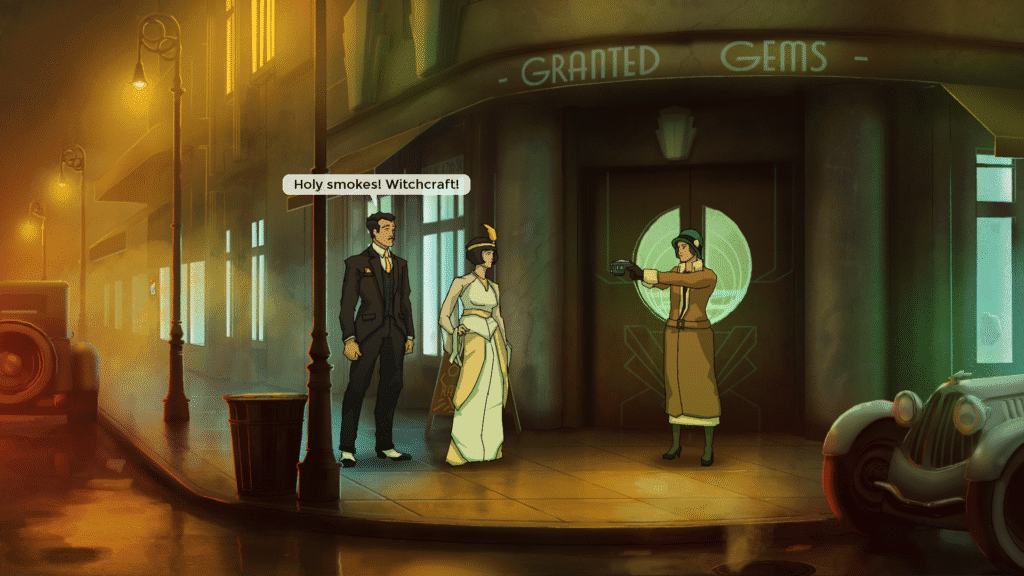

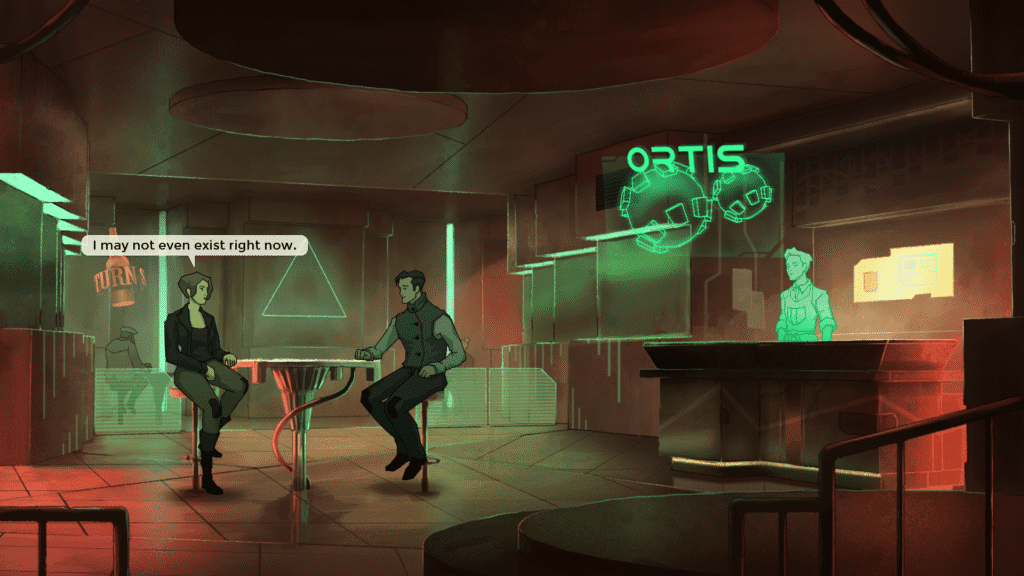

Let’s talk about how Old Skies looks. At first glance, it’s modest—perhaps even outdated by some standards. Gone are the nostalgic pixelations of Blackwell or Unavowed. Instead, this is Wadjet Eye’s first high-definition outing, rendered in clean lines and hand-painted backgrounds that channel the aesthetic of a graphic novel more than a video game. And I’ll admit, the character models took time to grow on me. Their comic-book expressiveness sometimes clashes with the rich, painterly backdrops.

But then… it happens. You land in 1920s New York, and the screen breathes. Smoke curls from jazz bars, electric signs buzz over cobblestone streets, and a soft orange haze blankets the world. Later, you find yourself on the eve of 9/11, staring up at the Twin Towers as a storm broods overhead. The camera lingers not on grandeur, but on detail—a scarf fluttering in a breeze, a diner glowing in the night, a woman staring at an old photo.

Old Skies doesn’t want to impress you. It wants to envelop you. It’s less about spectacle and more about atmosphere. And that’s why it works. Every era Fia visits feels distinct yet thematically cohesive, all filtered through a melancholic lens that reminds you: this world is always shifting. You just don’t always notice.

Soundtrack of a Shifting Reality

The music in Old Skies deserves more than a passing nod—it deserves applause. Thomas Regin’s score is not just background noise; it’s the emotional architecture of the game. Each time period is scored with haunting specificity. The 1870s hums with acoustic warmth. The 2040s pulse with retro-futuristic synths. The 1920s dance to a smoky saxophone that seems to echo from a speakeasy just out of frame.

But it’s not just the variety—it’s the precision. The music doesn’t intrude; it inhabits. It swells just as Fia begins to question herself, softens when a client recalls a childhood love, and quiets completely in those devastating beats when reality bends and breaks. The soundtrack doesn’t guide you—it shadows you.

And let’s not forget the voice acting. Sally Beaumont as Fia gives one of the most emotionally layered performances I’ve heard in years. She isn’t a quippy action heroine. She’s tired. Curious. Brave in a quiet, reluctant way. Her banter with Edwyn Tiong’s Nozzo is pure gold—sarcastic, vulnerable, and deeply lived-in. Their rapport is the kind you don’t script; you earn it, through understanding these characters not as archetypes, but as people.

Philosophical Ripples

Time travel, as a narrative device, has been done to death. It’s the realm of paradoxes, alternate timelines, multiverse mania. But Old Skies isn’t interested in techno-babble or big bangs. It’s interested in you. In us. It doesn’t ask, “What if you could change the past?” It asks, “Would it matter?”

ChronoZen’s algorithm—the arbiter of who matters in history—is dystopian in the most mundane way. You’re either a Low, Medium, or High-impact person. If you’re Low? Go ahead, erase them. Alter their lives. It won’t change the future. It’s bureaucracy at its most terrifying: cold, efficient, and terrifyingly logical.

And here lies the brilliance: the game doesn’t moralize. It observes. It shows you how easily ethics are outsourced to systems. How grief and hope and memory are commodities. How the past, once commodified, becomes a playground for the wealthy—and a graveyard for the rest.

Fia’s own story becomes a meditation on permanence. She is chronolocked—her memories immune to change—but everyone around her can shift in and out of existence. A lover she never met. A best friend she no longer remembers. Her mantra, “Focus on the job,” becomes an elegy. In trying to protect time, she loses her own.

A Genre Reborn: Industry Impact and Innovation

Old Skies is more than a great game. It’s a manifesto.

For a genre long thought obsolete, this is a spark of reinvention. No, it doesn’t break the mold mechanically. But narratively? Thematically? It redefines what a point-and-click adventure can be. Not as a museum piece, but as a living, evolving form of storytelling.

Wadjet Eye has always been the quiet titan of this space, and Old Skies cements that legacy. It doesn’t chase trends. It doesn’t pander. It dares to be slow, to be introspective, to ask you to sit with your choices. In an age of hyper-optimization and dopamine loops, that’s radical.

I expect its influence will be slow-burning. You won’t see its fingerprints tomorrow. But in five years? Ten? Developers will look back and realize: Old Skies did something new. Not by changing the rules, but by remembering why the rules mattered in the first place.

A Kind of Magic: The Player’s Emotional Odyssey

This is the part I struggle to articulate. How do you explain the ache in your chest when Fia sees a future that no longer exists? Or the joy of watching two lovers re-meet across centuries? Or the way a seemingly minor choice—returning a watch, fixing a portrait—echoes through timelines like a whispered prayer?

Old Skies isn’t about plot twists. It’s about emotional shifts. And my own journey through it was marked by more than just puzzles solved. It was marked by moments—small, crystalline, unforgettable.

There was a chapter where I had to let someone die, knowing they wouldn’t be remembered. Another where a client’s harmless nostalgia trip turned into a decades-long secret that shattered three lives. I wasn’t just playing a game. I was participating in grief. In joy. In the endless, exquisite fragility of time.

By the time the credits rolled, I didn’t want to go back in time. I wanted to stay—not because the world was perfect, but because it was mine.

On a technical front, Old Skies is a paradox in its own right—old-school in its soul, yet remarkably modern in its polish. Running on PC, the game was smooth as silk. No crashes, no load stutters, no UI hiccups. Every interaction was intuitive, with streamlined mouse controls and a minimalist interface that never got in the way of immersion.

The game’s commitment to accessibility is also commendable. You can tweak subtitles, speech text sizes, and volume mixes. There’s controller support if you prefer it. It’s clear that Wadjet Eye wants you to focus on the story, not wrestle with how to click on it.

But let’s not sugarcoat the few areas where Old Skies stumbles. While the loop-death mechanic is conceptually brilliant, its implementation occasionally flirts with frustration. A few sequences—in particular, a drawn-out safe cracking scene and a death-dodging brawl—lean a bit too hard into trial-and-error repetition. Even with narrative justification, reliving the same scenario six or seven times can test your patience.

But here’s the thing: these flaws are never deal-breakers. They’re the kind of smudges that remind you a game like this was crafted by humans—passionate, meticulous humans—rather than churned from a machine.

A Game That Lives Beyond Its Ending: Replayability and Longevity

Some games beg to be replayed because of mechanics—loot to grind, endings to unlock, levels to master. Old Skies is different. You come back to it not because you want a different outcome, but because you miss it. Like a novel whose underlined passages haunt you. Like a city you can’t help but visit one more time.

Each chapter, while linear in progression, holds secrets in its dialogue, its archive searches, its sidelong glances. Your first run will almost certainly miss things—a whispered detail about a lost sister, a painting that changes based on who you speak to, a timeline shift triggered by a seemingly innocuous question.

And then there’s the real replay value: emotional perspective. Knowing what Fia is heading toward changes how you interpret her every word on a second playthrough. Jokes that seemed light become layered with longing. Small decisions, like whether to hand someone a letter, take on devastating weight.

While the game doesn’t boast alternate endings or massive branching narratives, its replay value comes from reflection, not revision. It’s a rare thing in gaming: a story worth reliving not because you missed content, but because you want to feel it again.

A Masterpiece in Disguise: Misunderstood, Yet Monumental

Let’s be honest—Old Skies won’t make every “Game of the Year” list. It doesn’t scream for attention. Its marketing isn’t aggressive. It doesn’t have 4K explosions or roguelike replayability. And that’s exactly why it might be overlooked.

But I am here, passionately, to say this: Old Skies is one of the most important games of the year.

It deserves to be studied for how it handles time travel without sensationalism. For how it builds emotional stakes without melodrama. For how it crafts a world not from spectacle, but from subtlety.

It will be misunderstood, even dismissed, by some. Those seeking fast gratification or sandbox chaos will likely bounce off. But for those who stay—those who sink into its world with patience and open-hearted curiosity—it will not just resonate. It will linger. In memory. In mood. In meaning.

It is not merely a game. It is an experience. A conversation about grief, identity, history, and the invisible threads that connect us across time.

If you’re looking for comparisons, Old Skies feels like the lovechild of Life is Strange, The Forgotten City, and Day of the Tentacle, raised with the philosophical gravitas of Twelve Minutes but without its cynicism. It has the ethical complexity of Disco Elysium, yet it whispers where that game screams.

And yes, fans of Wadjet Eye’s Unavowed will find familiar fingerprints here—sharp writing, layered characters, quiet magic. But where Unavowed felt like an ensemble stage drama, Old Skies is a solo sonata. It’s about one voice—Fia’s—and the echo it leaves across history.

Unlike many time travel stories (Bioshock Infinite, Quantum Break), which delight in their high-concept metaphysics, Old Skies keeps things grounded. It doesn’t ask what’s possible. It asks what’s right. What’s human. And in doing so, it finds a moral and emotional clarity most games only dream of.

It’s not flashy, but it’s fearless. And in that way, it’s utterly, beautifully unique.

I don’t write reviews like this often. Most games don’t demand it. But Old Skies is something special. It deserves more than just stars or scores. It deserves players—ones who will meet it on its terms. Ones who will risk boredom for beauty, who will trade action for empathy, who will listen more than they click.

So here is my plea: play this game. Don’t rush it. Don’t multi-task. Give it the time it asks for, and it will repay you tenfold. Let yourself feel it. Let yourself be Fia Quinn—not as a hero, but as a human being navigating the strangest of realities: her own emotional truth.

You may not weep at the ending as I did. You may not see yourself in Fia’s journey. But I promise you this: you will not forget her. Or the clients. Or the music. Or the moment you realized time was not the enemy. Indifference was.

Give Old Skies your time. And in return, it will give you a little bit of eternity.

A Legacy Written in Loops

If video games are an art form—and they are—then Old Skies is its literary novel. Not the kind that storms bestseller lists or spawns sequels, but the kind that’s passed from friend to friend, spoken of in reverent tones, rediscovered in dorm rooms and lonely apartments, and cherished in quietude.

It is a work of patience, grace, and human tenderness. It asks not just what we would do with time travel, but what time travel does to us. It’s about choices, yes—but not the ones you can map out with binary morality meters. It’s about the little decisions. The ones we make every day. The ones we live with.

I started Old Skies with skepticism. I ended it with a full heart, misty eyes, and a newfound admiration for how far the point-and-click genre can go—not in scale, but in soul.

Dave Gilbert and Wadjet Eye Games have not merely created a game. They’ve created a legacy. And as Fia Quinn knows better than anyone, that’s something even time can’t erase.

Old Skies is out today for PC, Mac and Linux on Steam and GOG. A Switch version has been delayed.

Platform reviewed on: PC (Review code was provided by the game’s publisher.)

Price: $20, ₹880